A country’s art can say a lot about their history. Specifically, when this history is shaped by conflict and war.

Seeing as that Colombia’s history is deeply carved by its political conflict, its art has many times been the best way to process and digest the occurrences.

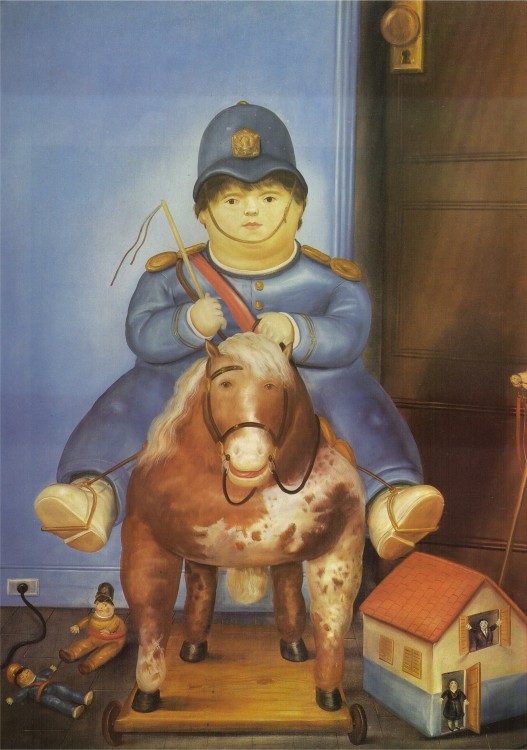

Such is the case for the painter and sculptor Fernando Botero, whose longevity has led to the observation and representation of many acts of political importance in the country, while at the same time a lot of non-politically related topics, like the art of childhood and traditional Antioquian values, being imprinted on canvas and sculptures.

The Man Behind the Curvy Phenomenon

I could argue that Fernando Botero is our most renowned artist. This, of course, depends on your definition of artist.

However, as a painter and sculptor, no Colombian man has made a name for himself in the world of international art quite like Botero. His voluptuous characters and objects became our postcards, your tourist photos, the souvenirs, and cultural references that have lasted for decades.

Generally, however, we know very little about Fernando Botero’s personality and traits. Unlike the very outspoken Fernando Vallejo (Antioquian novelist) Botero is a reserved man who mostly stays out of the limelight, with a few interviews here and there.

His art has taken central stage, which is probably something out of his own desire. Out of those who take a stroll through Museo de Antioquia, few remember that his first name is Luis and his second last name is Angulo, or know that he has a large, close, family. His daughter has been the curator for some of his work on occasion.

His accent is extremely paisa, he looks younger than he is, he is polite and charismatic. (or at least he seems to be)

He was the middle child and was sent to a matador school for two years in his youth. His first illustrations were published in El Colombiano. He was also fond of several (very Colombian) traditions like soccer and dancing and went to school with Gonzalo Arango, a well-known Colombian poet.

He won several Salon de Artistas awards during his life and studied art in Europe, familiarizing himself with the greatest of the continent, Pablo Picasso for one.

Fun fact: during an interview, Botero compared his rough experience in Iraq with the representation of Picasso’s Guernica, saying:

“It’s a representation for History. Though, I’m not comparing myself to Picasso, by any means, I am much better,” with a laugh.

He had four kids with his two wives (three with the first and one with the second), and the youngest died in an accident at a young age, which gave way to one of his dearest paintings Pedrito Botero.

My Personal Favorites

It took me a long time to appreciate visual art in general, being mostly a literature person, and especially art from home. However, the sheer amount of paintings, illustrations and sculptures made by Botero gives one a hint of his ingenious.

His sculptures are flawless. His donations to the city in Parque Botero and Parque San Antonio are works that are made to be stared at and interacted with all day, and they are. His messages about the resistance of the Colombian people are well heard.

For example, let’s think back to the Bird Statue bombed in ’95 and its replacement standing next to- or better- supporting the former. Simple acts like these make Fernando Botero the artist of the people, he lives the hard times along the rest of us.

photo from www.eladerezo.com

I also really love his family portraits, especially those that seem a little odd, with quirky characters or objects placed in the corners, and the proportions of the adults to the kids, though the latter don’t have any childish facial features-they’re small adults, like in medieval art.

All these things, however, seem to be placed very much on purpose.

His still lifes- oranges and pastries galore- are also extremely endearing and draw the eye with pastel colors and perfect voluminous roundedness that we know and love.

The Paintings of Abu Ghraib

Donated finally to the University of California at Berkeley, the paintings were first rejected by every museum in the U.S., The Washington Post’s cultural critic even questioned the nature of the 87 drawings and paintings of the tragedy, given that he “had not been a painter of deep thought in the past”.

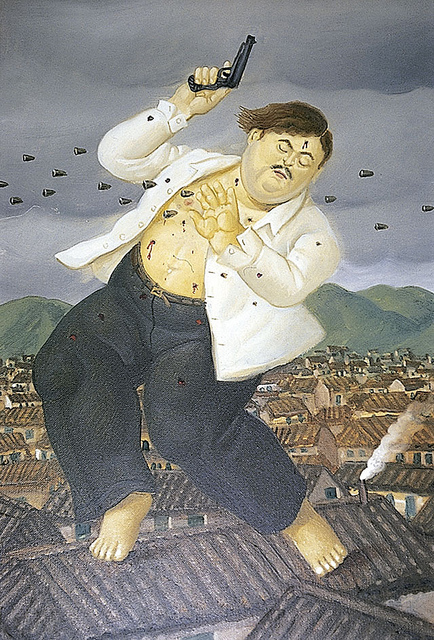

For an artist who titles paintings using words like “violence” and “massacre” and takes to topics like Pablo Escobar, I’d argue that he’s hardly a lightweight.

The Paintings of Abu Ghraib feature men being tortured, humiliated and scorned. Botero traveled to Iraq to witness the events and painted these works to have something to show for it, not to make money or to make a name for himself, (He already has sufficient money and reputation.) He wanted a light to shine on the inhumane acts of Abu Ghraib.

The New York Times had to say about it that,

“They may not be masterpieces, but that may not matter. They are among Mr. Botero’s best work, and in an art world where responses to the Iraq war have been scarce — literal or obscure — they stand out.”

The Paintings of Abu Ghraib are special because they are representations, as opposed to photographs taken that reveal and shame the subjects of them. They maintain an anonymity and a dignity otherwise lost.

They were only shown in the U.S. for the first time after he called a friend asking for the favor of taking some in his gallery in New York. Afer being donated to Berkeley, the University loaned it for a showing in Vienna.

When accused of anti-Americanism he simply responded:

“Anti-American it’s not,” Botero said emphatically. “Anti-brutality, anti-inhumanity, yes. I follow politics very closely. I read several newspapers every day. And I have a great admiration for this country. I’m sure the vast majority of people here don’t approve of this. And the American press is the one that told the world this is going on. You have freedom of the press that makes such a thing possible.” (Source SF Gate)

Colombian Violence

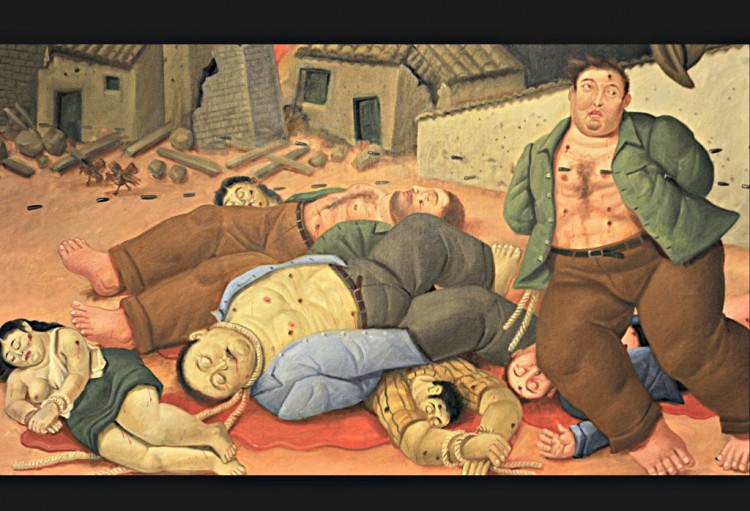

And it’s not the first time he takes hands a looking glass to a society that’s betraying its human nature.

“Art is important,” Botero said, “because when people start to forget, art reminds them what happened.” (Source SF Gate)

His representations of the Colombian period of La Violencia still hold Colombia to the history it so longingly hopes to erase. The paintings and illustrations of the hard periods of Colombian history are diverse and numerous and most are available for viewing at the Museo de Antioquia.

Photo taken from www.cromos.com

Is it possible that our history would be forgotten if not for these paintings? Do they make a difference in the collective memory and hold a standard for the future? I’d like to believe so.

I’d also like to see Botero live for many years longer, I’d like to see him modernize the Colombian Family portrait, I’d like to set them side to side.

But most of all, I’d like to return to Museo de Antioquia and visit his work again real soon.

I really enjoy Boteros work. His stuff can be found everywhere in Colomnbia. His paintings tell a rich of history of his home country. I really love and enjoy his museum in Bogota as well. Good subject and well written ?

!! Awesome !!

!! Awesome !!!

Way back in the ’70s (in San Francisco) I bought a very small Botero sculpture of a bronz pig; it was all I could afford at the time, but it was absolutely irresistable; it still occupies an important place on my mantle; I will always cherish it; if I ever get to Medellín, Plaza Botero will be a destination for both the first and the last day.

Botero.. El Colombiano mas importante de la historia artistica de la Patria del Sagrado Corazon de Jesus. Yo, un paisa eternamente emamorado de su arte, sus pinturas y sus mujeres gordas me acuerdan de las historias de las Senoras del barrio Lovaina en Medellin de aquellas epocas…ustedes comprenden verdad?