The following is a guest post by Andrew.

Hi, I’m Andrew and I’ve been teaching myself Spanish for about four years now.

In the process of doing that I’ve met and talked to tons of native Spanish speakers and also lots of other language learners, and in that time I’ve learned, well not only a lot of Spanish, but also a lot about the most common mistakes that native English speakers tend to make in speaking Spanish.

These are things that have formed a pattern I’ve noticed after having interacted with lots of other people who are learning Spanish and also having had several native Spanish speakers mention them to me.

The same mistakes tend to happen over and over with different people because of the way the English and Spanish languages work, and so there are common misunderstandings and mistranslations that happen over and over.

I know that Latin America is a very popular backpacking destination and most backpackers will make sure they learn at least a little rudimentary Spanish before they go, but of course most of them are learning it from some type of course or class and consequently they’ll tend to make many of the errors common to English speakers learning Spanish.

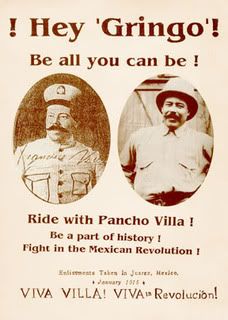

Here are what I’ve found are the 10 most common errors that peg you as a “gringo” (non-derogatory term for a foreign, typically English-speaking, person).

1. The Pronunciation of “Y” and “ll”

In Peninsular Spanish (Spanish as it’s used in Spain), and in what might be called “proper” or “formal” Spanish, “y” is pronounced exactly as it would be in English. This is also how it’s taught in almost all Spanish classes, home-learning courses (Pimsleur, Rosetta Stone, etc.), and in textbooks because it’s the “technically correct” way of doing it.

However, in most of Latin America, it’s not pronounced like that, it’s pronounced with a “j” sound, e.g. “yo” (meaning “I” in Spanish) is pronounced “joe”, and the same thing goes for the double-L: “ll”, as in “llegar”, which would be pronounced as “yay-gar” in Spain but “jay-gar” in most of Latin America.

This is probably the most common thing that people do in Latin America that pegs them as a gringo straight away (if your Spanish is really good they might mistake you for a Spaniard, but it’s unlikely), and it’s something that typically takes quite a bit of time and effort to correct because they’ve been saying “My name is Bob” in Spanish as “May ya-mo Bob” (proper spelling would be “Me llamo Bob”) ever since they started learning Spanish and now they need to switch over to “Me ja-mo Bob”.

If you’re planning on using your Spanish in Latin America, as most backpackers are (or they at least mostly plan to use it there), get started right and teach yourself to pronounce it the way the natives do.

It should also be noted that Argentinians in particular and Uruguayans, as well, pronounce it a little differently with a sort of “zh/sh” sound, so it would be “May sh-amo Bob”.

2. That Damned “R”

You knew this would be on the list. I understand some people have a really hard time rolling their “r”s properly, but it’s something you need to be able to do, and quickly and smoothly on demand, if you want to sound right.

If an “r” is at the beginning of the sentence, as in “Rojo”, or it’s a double-r, as in “cigarro”, then it gets trilled (in lay terms it gets “rolled” twice), whereas if it’s a single “r” anywhere else then it just gets what’s called an alveolar flap (in lay terms it gets “rolled” once).

Here’s a fantastic video that shows you precisely how to learn how to roll your “r”s:

A nifty little children’s tongue-twister that’s used to help them practice their “r”s is the following (nearly every Spanish-speaker has heard this one):

Erre con Erre Cigarro

Erre con Erre Barril

Rápido ruedan las ruedas

Sobre los rieles del ferrocarril

Which translates to:

R with R cigar

R with R barrel

Quickly run the cars,

Over the rails of the railroad.

3. “C” and “Z”

They’re pronounced exactly the same. They don’t really use our pronunciation of the “z” for anything, their “z” is pronounced like an “s” would be in English, as is their soft “c”. A “c” in “co-”, “cu-”, or “ca-” like “carro” or “cumplir” is the hard “c” and is pronounced as we would a “k”. An example would be the Spanish word for “shoe”, “zapato”, which is pronounced “sa-pah-toe”.

4. Quit Saying “Yo” So Much

Because we will always use a personal pronoun in English, such as “I” or “you”, when referring to that person, native English-speakers will tend to carry the same habit over to Spanish with disastrous results.

Due to the way the verb conjugations work in Spanish, you frequently don’t need to use a pronoun to indicate who did what, the very conjugation of the verb alone, or the conjugation of it in conjunction with the context, will be sufficient for everyone to know who you’re talking about, and consequently Spanish-speakers will never use a pronoun that isn’t necessary, and since the first person conjugation (the “yo” conjugation) is never used with anything other than “yo”, “yo” is never really necessary for everyone to know that you’re talking about yourself and so it’s never used unless you want to emphasize that you’re talking about yourself.

This results in a particularly bad phenomenon of gringos using “yo” way, way, way too much, and it makes them sound self-centered, it’s like constantly stressing the “I” in English, e.g.:

“I didn’t like it.”

“I went there the other day…”

“I don’t want any.”

See how that sounds? Only use “yo” if you want to stress the fact that you’re talking about yourself. So if you wanted to say “I can’t do it” normally, you’d say “No puedo hacerlo”, instead of “Yo no puedo hacerlo” which sounds like “I can’t do it” (implying that someone else can). Quit saying “yo” so much.

5. Quit Pronouncing the “H”

They never, ever, under any circumstances, pronounce the “h” in Spanish, it’s always silent.

“Hora” is pronounced “ora”, “yo hablo español” is pronounced “joe ah-blow ess-pan-yol”, etc.

Don’t pronounce the “h”.

Ever.

6. “Embarazada” means “Pregnant”, not “Embarassed”

Ohhh this is my favorite one by far, it’s one of the most common false friends, and it’s definitely the funniest.

Most words in Spanish that sound like a certain English word, do, in fact, mean that word or something similar, but you really have to be careful because a good 20-30% of them don’t, so don’t assume it does, check and make sure first. Many a gringo before you has attempted to express the fact that they were embarrassed by saying “¡Estoy tanta embarazada!”…well, if you weren’t embarrassed before, you are now, haha. You just said “I’m so pregnant!”.

The correct way to say “I’m so embarrassed” is “¡Me da tanta vergüenza!”, which literally means “It gives me such shame!”.

I can’t possibly fit in even a short list of Spanish-English false friends, there are tons of them, just note what I said before about not automatically assuming that a word which looks a lot like an English word you know means the same thing as that word, check first.

7. Mixing Up “Preguntar” and “Pedir”

“Preguntar” means “to ask”, “pedir” means “to ask or order”, and there’s the key: “to order”.

“Preguntar” is used when you want to ask something (when you want to know something, you’re asking for information), “pedir” is when you want to ask for something, e.g. you want to order anything in a restaurant, bar, cafe, etc.

8. Mixing Up “Por” and “Para”

I still do this one occasionally, learning the rules is one thing, always remembering to apply them while you’re talking, on the fly, is quite another. Here are the basic guidelines:

Use “por” for:

- In support of something: “Trabajamos por el gobierno” = “We work for the government”

- Whenever you would use “per”: “Cuesta dos pesos por persona” = “It costs two pesos per person”.

- To express who did what: “Pintó por José” = “It was painted by José”.

- Indicating means of transportation: “Él llegó por avión” = “He arrived by plane”

Use “para” for:

- Expressing who/what something is for (as in, for someone or something’s benefit): “El regalo es para tú” = “The gift is for you”

- Expressing “in order to”: “Para aprender español, se necesita practicar mucho” = “In order to learn Spanish, you need to practice a lot”

- Expressing “to” as in direction: “Voy para Bogotá” = “I’m going to Bogotá”

- Saying “by” in reference to a specific time something has to be done by: “El jefe dice que necesita eso para mañana” = “The boss says that he needs that by tomorrow”

9. It’s Almost Always “Mucho Gusto”, Not “Encantado”

I think most textbooks now have had this taken out of them, but I know there are definitely still some floating around out there (my Spanish class in college had one that did this, and that was only a few years ago) that do this: when you meet someone and they introduce themselves, the proper way of saying “Nice to meet you” is “Mucho gusto”, not “encantado”.

“Encantado” means “enchanted” and carries about the same connotation in Spanish as saying “Enchanted” upon meeting someone in English would. It’s still used, in Spanish, in very formal situations, but unless you’re meeting local high-up politicians at a black-tie event, I wouldn’t. Just don’t use it, stick with “mucho gusto”, if you do you’ll be fine 99.999% of the time.

10. “Usted” vs. “Tú”

This one really messes with beginners, but it’s actually quite easily dealt with by using one simple rule: if you would use “Mr./Mrs.” with this person, use “usted”, otherwise use “tú”.

The mistake most gringos make is using “usted” too much instead of not enough, they “usted” everybody, the cat, and the kitchen sink for fear of offending anyone and it seems like they’re maybe a bit uptight or something. Would you call your bartender “Mr. Smith” or “Joe”? “Joe”, right? Ok, then just use “tú” with the guy straight away. How about your new neighbor? Well, you’d probably start off with “Mr. Garcia” and then, after you get to know each other, you’d start calling him “Juan”, well then you use “usted” to start off with and the moment that you would start calling him “Juan” is when you’d switch to “tú”, easy-peasy.

“Vos” is just a new pronoun that’s caught on in some countries (primarily Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and parts of Colombia) that’s used in place of “tú”, so just take what I said above for those countries and switch out “vos” for “tú”, simple.

Bonus: Clothes

My Top 9 Ways to Avoid Looking Like a Gringo in Latin America includes a few basic tips that will keep you from being pegged as one on sight, at least they’ll have to hear you talk before they realize that you’re one.

__________

About the Author: Andrew runs a blog on how to learn spanish and has been learning Spanish on his own for nearly four years now. He posts information on his site aimed specifically at people who want to teach themselves Spanish on their own, from home, including things like using popular media to learn Spanish as in his recent series on learning Spanish from Shakira’s music.

Dave

Another thing, in Medellin we use a lot the word “Molestar” but it doesn`t mean the same as “Molesting” in English, 😀

Saludos

In the ‘para y por’ section shouldn’t it be ‘El regalo es para ti‘?

“vos” is not a “new” pronoun,..it is actually the older one,in most countries “tu” has replaced it

Yes “vos” is not a “new” pronoun. Vos is used extensively in countries like Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Vos is also used some in some parts of Colombia like the West (Pacific Coast) in Chocó, Valle del Cauca, Cauca and Nariño. You will also find it used sometimes in the Paisa Region in the center of the country (it is not used in my Spanish classes at Universidad EAFIT). You can also find vos used in places like Cesar and La Guajira.

The use of vos has pretty much disappeared in several countries including Spain, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and the U.S.